Sewa News Opinion Page

A pointless and potentially dangerous controversy has recently been triggered by an argument about the extent of rights to be enjoyed by dual citizens of Sierra Leone.

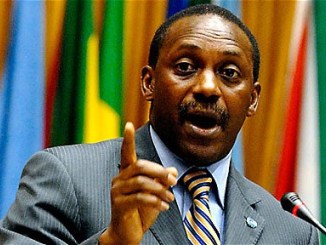

This is in part because of the ruling All Peoples Congress has opportunistically, in an effort to disfranchise its most potent rival the National Grand Coalition’s standard-bearer Dr. Kandeh Kolleh Yumkellah (see photo)), seized upon Francis Gabbidon’s ill-timed and wrongheaded opinion that a justly long-ignored provision in the 1991 constitution should be enforced.

In his article, Mr. Francis Gabbidon, a former ombudsman, cited Section 76(1) of the 1991 Constitution which states that no naturalized citizen of Sierra Leone or a “citizen of a country other than Sierra Leone having become such a citizen voluntarily” can contest an election to become a member of parliament and by extension president and cabinet minister.

This interpretation misunderstands the letter, context, and spirit of this provision and the intent of the 2006 Citizenship Amendment Act. Section 76(1) of the constitution does not deal with or in any way apply to citizenship acquired by birth and can in no way be used as a basis to disqualify Dr. Yumkella who is a citizen by birth.

The overriding consideration for enacting the 1991 constitution was to replace the one-party constitution of 1978, which everyone acknowledged had become a ghastly failure. Dual citizenship was not an issue. A brutal civil war whose foundation had been laid by the one-party state had just begun, and over its more than 10-year deadly course, tens of thousands of Sierra Leoneans fled the country to seek refuge elsewhere.

A large number of them naturally acquired the citizenship of their host country. But they never forgot the home they had fled, and part of the reason why they acquired their host country’s citizenship was to be empowered enough to be able to travel in and out of the country they had fled and to be able to support loved ones there.

President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah, who had himself been forced to leave Sierra Leone by the vindictive actions of President Siaka Stevens in the late 1960s after a successful career as a civil servant, readily acknowledged this fact. In 2006, his Sierra Leone Peoples Party pushed through an amendment to the 1973 citizenship Act recognising dual citizenship, in effect restoring all rights to native-born Sierra Leoneans who had renounced their Sierra Leonean citizenship.

The 2006 dual citizenship act amended the Sierra Leone Citizenship Act 1973 in a number of substantive ways. First, it granted the right of dual citizenship. Secondly, it provided for citizenship by birth to be acquired directly through the mother. The third was to allow for the automatic resumption by any citizen of Sierra Leone who “acquired the citizenship of any foreign country… by any voluntary or formal act.”

There is a wider and much deeper context, however, to the dual citizenship issue that might serve to clarify the issue further by revealing the utter fatuity of Mr. Gabbidon’s position. Dual citizenship as a political issue certainly has nothing to do with a concern about citizens “pledging allegiance” to another country, as local vanity, demagoguery or sheer capriciousness have led some people and the APC government, many of whose cabinet ministers have dual citizenship, to embrace Mr. Gabbidon’s interpretation.

The concern about dual citizenship is rooted in an all-consuming anxiety that gripped the dissolving British colonial empire: the fear that darker skinned or swarthy peoples from its colonies, a large number of whom were British subjects, could automatically claim British citizenship if a specific measure to deprive them of that option was not taken.

The problem, as the British saw it, began in 1947 with the independence of India. The British saw no such problem with respect to the so-called White Dominions – Canada, which became independent in 1867, Australia in 1901, and New Zealand in 1907. The idea that millions of impoverished Indians would flood the little island suddenly became a major political problem, and barely a year after India’s independence, parliament passed the British Nationality Act of 1948 establishing a brand new status it sedately called “citizen of the United Kingdom and colonies”.

This status, which Margaret Thatcher abolished in 1981, specified British nationality to persons born in the United Kingdom and those places that were still British colonies or dominions; the law also created the category of “British protected person” for so-called natives of British protectorates who enjoyed limited rights of citizenship.

The law immediately excluded everyone having Indian nationality from British citizenship.

African and other colonies were dealt with in a more subtle and ingenious way as they, too, demanded independence: the British made sure that the constitutions of all their colonies emerging into nationhood or independence more or less conformed to a mode devised at Lancaster House in London (which indeed became the place where all the independence negotiations were subsequently concluded): full citizenship was restricted for the most part to people of ‘negro descent” – thus excluding Lebanese in Sierra Leone, many of whom quickly acquired British passports – and primarily to those who were born in that territory at the time of independence.

Britain still maintained its own dual citizenship system, but into the constitutions of the emerging nations were inserted provisions that foreclosed the option of dual citizenship – so that the Africans would have to make a choice of British or their nation’s citizenship. At that moment of great pride and optimism, of course, many chose their new country’s citizenship, giving up their claims to British nationality.

The idea that the leadership of the APC government is now drawing upon this discriminatory and obnoxious template to deprive their fellow citizens of rights that should be taken for granted is outrageous and must be rejected.

If the National Elections Commission or the Supreme Court accepts the former Attorney-General and Deputy Secretary General of the APC’s Frank Kargbo’s contention that dual citizens, some of whom are currently cabinet ministers, may not even vote, this would be a serious reversal of all the gains in expanded rights and opportunities for citizens of Sierra Leone that have been made since the collapse of the one-party state.

An academic and writer, Dr. Lansana Gberie has written on conflict, conflict management, human rights and peacebuilding in Africa. He is also the author of A Dirty War in West Africa: The RUF and the Destruction of Sierra Leone (London: Hurst 2005).

Comments